Many years ago, I started my musical career singing, or maybe I should say screaming, with a Punk band, then eventually, through some very complicated in-between steps, I ended singing Opera, then on to musical theatre, then swinging it with jazz groups, and nowadays, mostly, I’m singing my own original songs. However through all of that, I've been enchanted, inspired, and more than a little obsessed, by the music of Kurt Julien Weil. I've sung Weill’s music in lovely concert halls and dark saloons, I've sung his music accompanied by rock guitar, punk bands and jazz quartets and I've never grown tired of his songs. And I believe that is because Kurt Weill was a wild and crazy Punk Rocker, and that’s what I intend to prove in this episode.

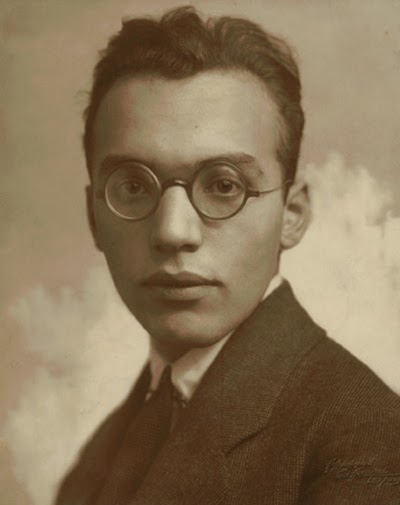

the young Kurt Julien Weill

Welcome to The Weimar Spectacle, where I explore the brief and extraordinary life of the Weimar Republic. I’m Bremner Fletcher, singer, actor and theatre maker. I’ve spent years performing songs and theatre from the Weimar period, and I’m inspired and maybe more than a little obsessed by that moment in time. You’ll find a transcript of this episode and images from the episode on my website at bremnersings.com

So, my big, big idea for these podcasts, is that the Weimar Republic invented everything about the modern world, and we are all still dealing with the possibilities and problems it gave to us. To prove this possibly unprovable idea, I’ll be exploring the arts, politics, science, architecture, social innovations of the Weimar period, and of course, the terrible and irresistible rise of the Nazi Party. So, if you’re a Velvet Underground fan who wants to know how and why Lou Reed ripped off Bertolt Brecht’s poetry, or maybe you’re an art history student curious about Andy Warhol’s roots in the Weimar mass spectacle, then this is the podcast for you!

I became aware of Kurt Weill's music around the same time I was sticking safety pins in my leather jacket, dying my hair blue and leaping into the mosh pit for bands like Black Flag and the Dead Kennedy’s. Something in Weill resonated for me. I knew nothing about Germany between the wars, nothing about the social and political turmoil that produced artists like Weill, Brecht, and Otto Dix and Walter Benjamin. But right from the start, my brain put Kurt Weill into the ranks of real musicians. Kurt Weill was a Punk Rocker!

Yet now, many years later, I wonder if I can express that a bit more better. Now that I’ve read the biographies, the letters, listened to early works and last works, studied his musicals that were a success and the ones that were disasters. Now that I have sung so many of his wondrous, complex songs.

Because Kurt Weill wrote extraordinary songs. Mostly for musical theatre shows, but his songs live on outside of them. He wrote songs of desire and love, hatred and anger and hope and renewal. And why did Weill have such eclectic brilliance? Well, I think that unlike other musical theatre writers like Gershwin or Porter or Rodgers and Hammerstein, Kurt Weill was forever marked by his life in Weimar Germany in the 20's when that country was being ripped apart by violence, racism, economic strife and yet was at the same time idealistically striving for a new beginning. In response, Weill learned to shift between the sublime and the shocking in a heartbeat.

I've been in Berlin a couple of times. Once, a long time ago, I hitchhiked to Berlin through Bulgaria and Romania, when they were still run by the Soviets. I was in Istanbul and on the highway just outside, this German guy picked me up in his Volkswagon van and drove me all the way to Berlin on a shortcut through these two authoritarian police states. Very generous of him, don’t you think? I just kinda wish he'd told me about the 4 kilos of hashish stashed under the trunk that he was also driving to Berlin. Or, then again, maybe I'm glad he didn't tell me. I would have died from fear. When we got to Berlin, it was grey, and damp, and I stayed in a half ruined squat with other punk rockers and anarchists and we drank cheap vodka out of huge bottles with tinfoil lids. That is to say, once you’d peeled back the top of those large bottles, there was no way to close them. I went back a few years ago, to see the new shiny Berlin, filled with art and music and money and shopping malls and wild ambitious goals.

But nothing compares with Berlin in the 20’s because there has never been a city like it before, or since. Imagine the most exciting city in the world. And the most terrifying. WW1's just ended. 15 million men dead. And Berlin’s streets are a horror movie of wounded veterans crawling and begging. Inflation goes insane. At once point, 320 million German Marks buys a pound of butter. There are 6000 licensed prostitutes. 20,000 unlicensed ones. You want to get tied up - there's an entire neighbourhood for that. You like boys, you like girls, girls who like girls, boys who like boys, boys who like animals? Entire neighbourhoods for that!

But most importantly, there are dozens of cabarets and theatres and performance space that are inventing modern music, modern theatre and modern art.

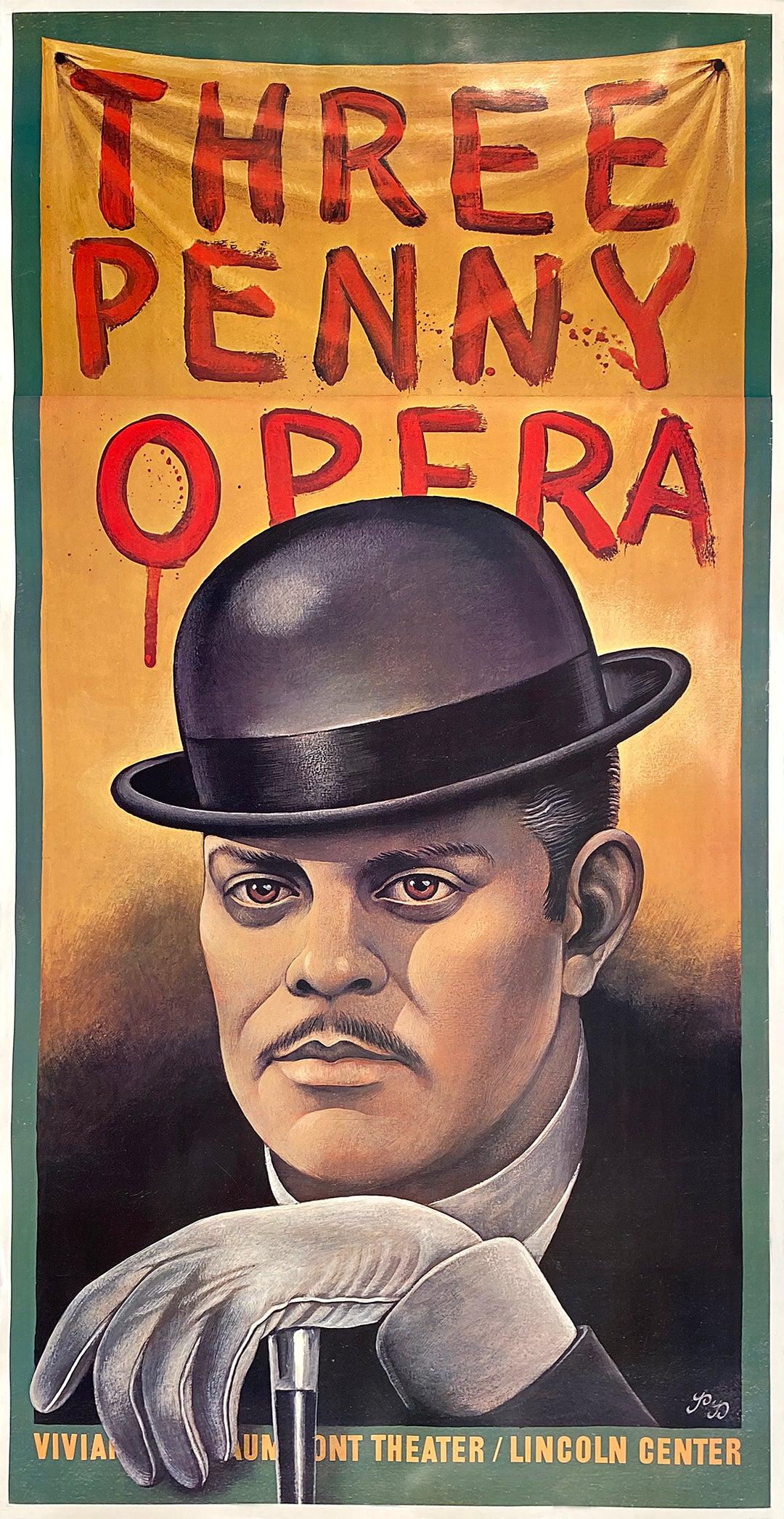

And into this amazing chaos walks Kurt Weill, the 20 year old musical son of an orthodox Rabbi. Hooks up with Lotte Lenya - part time actress, part time cleaning woman, part time prostitute. They hook up with Bertolt Brecht, professional angry young man, and together they write The Three Penny Opera, about a city where murderers and pickpockets are in charge. And god dammit, it sounds like they had such a great time.

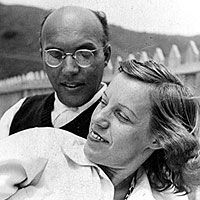

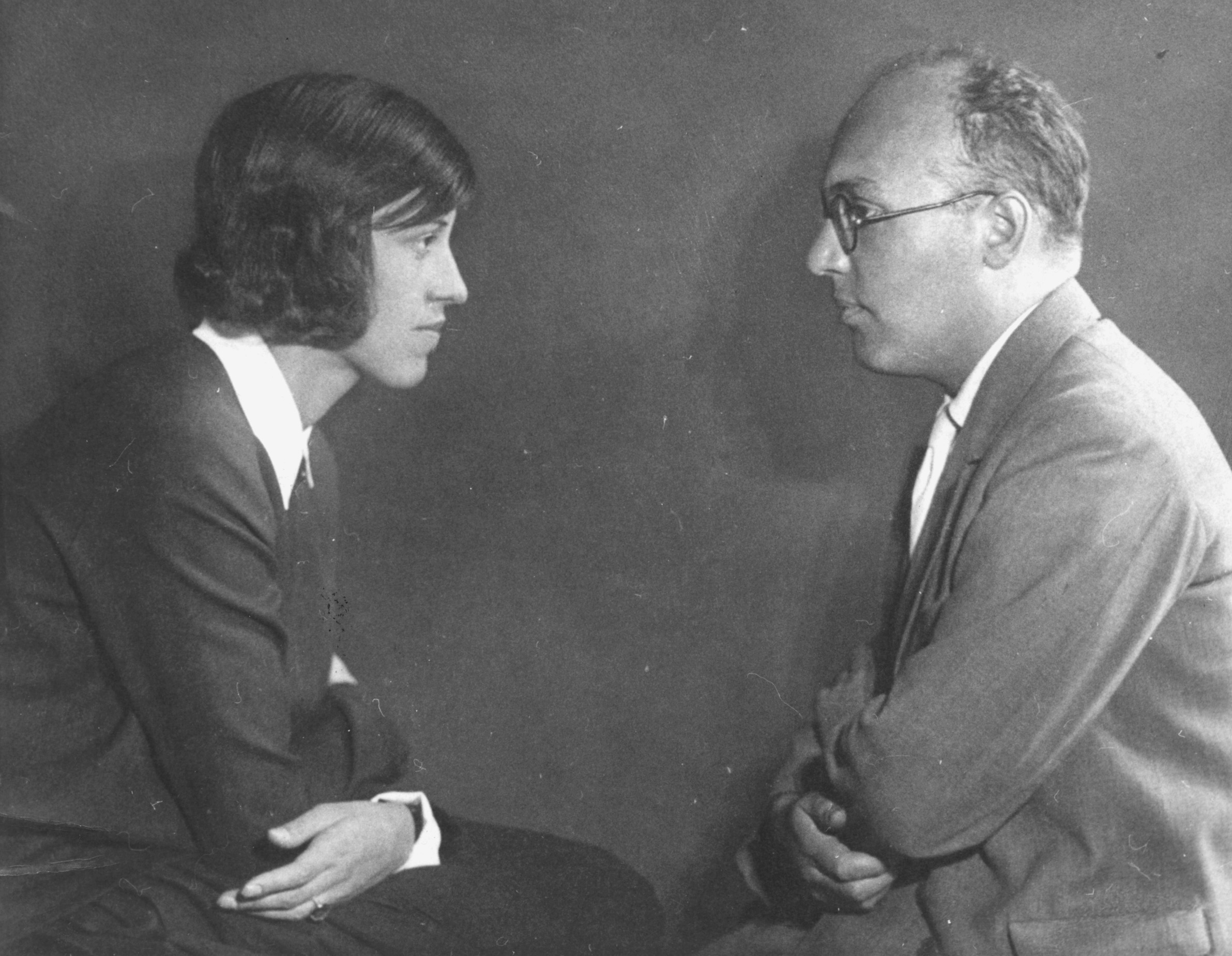

Weill and Lenya

I love this quote from one of Lotte Lenya's letters - she says, let me try my mock german accent here - ‘Often I went along with Kurt to Brecht’s studio. They invited us all to contribute our ideas. Out of these prolonged, fantastic and often hilarious discussions, Brecht and Kurt would draw what suited them. Now that all this is history, and solemn critical essays and books pour out in increasing volume, who would know how much fun went into all of this?”

For those of you who don’t know Lenya, as much as I am so proud of my recordings of Weill’s songs, I have to say her interpretations of are classics, so check them out, and whether or not you’re a fan, you might have actually seen her in person, since many years later, she has her moment of fame when she appears in a Bond Movie, From Russia With Love, as the deeply sadistic, Russian villain, Rosa Klebb. Her work in the film is just wonderful and verging on totally over the top evil camp.

the evil Rosa Klebb

Lenya showing her less evil side as she gets her makeup fixed

Kurt Weill was born in Dessau, Germany, and, as I said, the son of an Orthodox synagogue Cantor, music was in his bones and his upbringing. By the age of 12 he was already composing and producing concerts in the empty hall above his family’s home. And he studied with the most accomplished contemporary composers and teachers of his era, like Busoni, Hindemith and Albert Bing, Weill claimed that his experience conducting at the provincial theatre at Dessau, which mostly produced light operetta and comic shows was the most formative period of his life. And that dynamic between the contemporary and the popular rests as a source of energy for his whole career.

I can only imagine the effect that arriving from a provincial town into the creative madness of post-WW1 Berlin must have had on a young artist. I think ‘mind-blown’, might be a reasonable assumption. Normally he would have followed the expected path of a classical composer: that is - advanced studies with stars of the period, some study abroad, compositions premiering at festivals, and eventually a position as a teacher or the acclaimed head of a department in a university. That didn’t happen. Weill decided early his great love was music theatre, and he found the strict classical rules of traditional opera to be stifling. He wrote, “With the Three Penny Opera we reach a public which either did not know us at all or thought us incapable of captivating listeners ... Opera was founded as an aristocratic form of art ... If the framework of opera is unable to withstand the impact of the age, then this framework must be destroyed ... In the Three Penny Opera, reconstruction was possible insofar as here we had a chance of starting from scratch.”

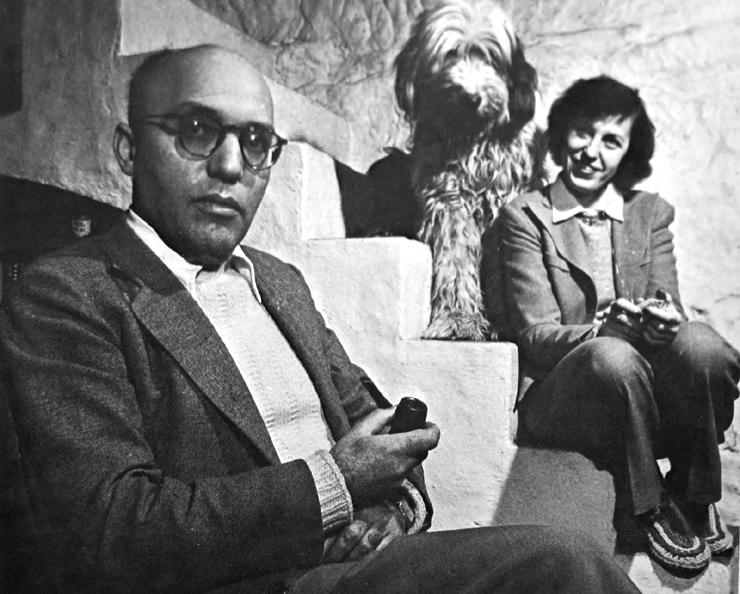

Brecht and Weill

Perhaps his friendship and partnership with the young writer and critic Bertolt Brecht should not have been surprising. All his life Weill searched for talented and innovative and socially committed collaborators, and Brecht was a rising star in Weimar’s literary scene. They create Three Penny Opera in 1929 and it is a Success Du Scandale and makes Weill, Brecht and Lenya into stars. The show is based on an piece of English music theatre from the 1700’s called The Beggar’s Opera, which in it’s time had also been a Success Du Scandale, and Three Penny also includes four Ballads by Francois Villon, the notorious criminal French poet from the middle ages.

the first performance of The Three Penny Opera

The original Beggar’s Opera had satirized the fad in London for an extremely mannered and foreign style of Italian Opera, and Brecht and Weill’s work likewise attacks the hypocrisy’s of Weimar society. And there is a lot to attack: Threepenny opera is written through 1928, and things in Germany are not looking good.

Already, in 1923, - the head of Germany’s steel industry had said ‘The German labour force must be ordered to work harder. A dictator must be found, equipped with the power to do whatever is necessary.’

Weill says, ‘Brecht and I toured factories and mines. then it became clear – the terrible horror down there, the boundless injustice that human beings have to endure, just so that Krupp Industries can add another 5 million to their 200 million a year – this needs to be said, and in such a way, indeed, that no one will ever forget it.'

Three Penny was a massive success.

So this is the moment I love. The moment all artists dream about. You become a star! Most of us labour in the show biz trenches all our life. But we all dream about a big hit. And for Kurt and Lotte and Brecht, that was threepenny opera. It changes everything. Lotte Lenya becomes a star. Kurt Weill becomes a household name. And they had fallen in love and started an extraordinary lifelong relationship that sustained them through so many trials to come. And, honestly, it was quite an odd relationship: because I think they were in love. I mean. It's hard to say... you know... they get married, divorced and remarried. And they have what seems like hundreds of lovers. So, I’m sure they were in love but sometimes, reading their letters, it's confusing.... let me quote from several of them:

“Dear Lenya, We’ve really solved the problem of living together, which is so terribly difficult for us, in a very beautiful and proper way… ”

“Dear Kurt! I picked up crab lice…. I got some stuff in a drugstore. Those trains are filled with soldiers and they are just dirty beyond belief”

“Dearest Lenya. you need a human being who belongs to you, 'cause there has to be someone to whom you don’t need to lie.... Such a step would not be possible without a strong commitment of what you call – with a shrug of your shoulders – ‘feelings’…. Let me be your pleasure boy…more than a friend, but less than a husband. ”

“Dear Kurt, I’m game for anything… and you could be completely independent. But you know that anyway.”

"Ah my dear Lenya, I believe we're the only married couple without problems"

well, whether or not Weill and Lenya were in love, they were definitely in lust - you can tell from the way they sign off their letter

Lenya writes at the end of a letter...

Oh, Weilchen, Glatzchen

which means...

Dear Weilly, my little Baldy

Weill writes...

Meine Blumchen

My Little flower

she says

Mein Schweenchen

My little piggy

and he says

Mein Warschi

My Cute Ass

she says

Mein Affenschwanz

My little Monkey tail

and, naturally, he replies with the endearing ‘Deiner Glatchen ich verbleibe in ausgezeichneter hochachtung, dein ergebener Affenschwanz

which means

Your little baldy, I remain in extraordinary high respect, with my highly erect and devoted little monkey tail held very high”

The next bit of Weill’s life is the bit I kind of hate. That’s when the fun stops and friendships falls apart. You know, when you work with a friend, it can be complicated. And sometimes success, instead of making it easier, makes it harder. I remember starting a theatre company with a bunch of bohemian friends and we created seasons of work with nothing and sweat and belief and bits of cardboard and energy drinks... and it was so much fun...and then, we got a huge cash grant for our next season. And everything changed.

And maybe success brought similar issues into Brecht and Weill's collaboration. Also, Brecht was not known as a man with a small ego, and perhaps he wasn’t so happy about Weill’s music getting all this attention. Year’s later, Lenya writes ‘My dear Weill. This shit with Brecht is just too funny for words. Good God. Sounds like in the old days when he tried to keep your name off the program. This pale faced flaming asshole, this Weissengrund. Its just beyond belief. The hell with them. You know what they would do, if you give in. Cut the music to pieces and make the whole thing cheap and ridiculous. This stupid Brecht, this backwoods philosopher. The letters from him soil our mailbox”

soooooo...I think we can safely say ...they had a little falling out.

However, before falling out completely, they manage to complete several pieces, though none have the impact of Three Penny. Among them is a show called Happy End, which is a flop, and doesn’t get performed again till the 1950’s, and also the three act opera, ‘The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny’. Which is an amazing piece, has some classic songs, and to it’s great credit was so hated by the Nazi Party that they send in demonstrators to disrupt the first performance.

At this point in Weimar Germany, the Nazis are growing in power and influence, and are using culture wars as a way to attack the entire foundation of the Weimar’s attempt to continue as a liberal democracy (a tactic which probably sounds terrifyingly familiar to anyone listening to this in 2024) and the Nazis do their best to make things difficult for any artist of whom they disapprove. Weill must have had some sense of what was coming: while on holiday in Switzerland, Weill opens up an account in case he needs to run.

However, Weill does seem like an optimist and he must have still hoped things would go differently, since he uses some money from his success to buy a home in Berlin. Now, this is before the days when Success in show business meant you could buy yourself a private jet and a 60 room house....success for Weill means that he has enough money to buy a little home. Weill writes to Lenya and says "the house is 7 Weissmanstrase, do you hear, 7! Our lucky number". Then one evening he comes home to find a note on his doorway. "What's a dirty little Jew like you moving into a nice neighbourhood like this".

So he runs. On the 21st of March, 1933, after he’s been tipped off the Nazis are about to arrest him. And it’s not just because he's Jewish. The Nazis, before they have the power to attack Jews and Homosexuals and Gypsies, they go for the artists. Adolph Hitler, who sadly enough for the history of the world, failed when he tried to become painter, says "anybody who paints the sky green, and the fields blue should to be sterilized". Taking art criticism to the extremes. Weill runs and never returns to Germany. Later the Nazis will hold public burning of his compositions.

Public book burning in Nazi Germany

A while after, Weill ends up in Vienna for one last performance of his work. Everyone is there, because everyone is running. German Artists, writers, film makers, poets. A local critic says, 'Everyone who counted in German Theatre met together for the last time at that show. And everyone knew it that it was the last day of the greatest decade of German Culture in the twentieth century"

Weill goes to Italy, Paris, London, then Paris. Searching for a home. And back home there is a war starting, troops pouring across the borders of Germany.

He goes to London to see if he can write for the musical theatre, however, the Times reviews Weill's work and writes. "It is hard to say which is weaker with Weill, the text or the music, probably the music, which does not even contain good second hand tunes. Weill writes a particularly nauseous kind of jazz... They say that every age gets the amusement it deserves. it is hard to believe that even Modern Europe deserves the music of Kurt Weill."

Bad reviews suck. You know, you always say they don't, but they do. And you remember the worst lines forever. But in Paris, it's even worse, in the middle of a concert of Weill's songs, a French composer, Florent Schmidt, stands up and starts to scream Heil Hitler until they stop the concert.

So Weill is in Paris. He's lost. He's broke. Lotte and he are divorced, though that may have been to make sure she was safe from being accused of marrying a Jew. She’s in Berlin, trying to sell the house, trying to smuggle money out of the country and Weill’s very alone. And he writes one of my favorite songs: Youkali, about looking for the perfect place to live.

There’s a ton of great versions of this song. I’ve recorded a couple of versions of this song, one in a studio in Paris with the amazing French music director and pianist Stan Cramer, and one in Edinburgh, with a jazz trio led by the wonderful Scottish pianist, David XXXXX – you can find those in the streaming world: and the words of that song are so poignant: for those of you who do not speak French, they go something like – ‘Youkali, is the land of our desires, happiness, pleasure, where we leave behind our cares and where our wishes and dreams are respected. It's an island at the end of everything. But it's just a crazy, dream. There is no Youkali.’

Through 1934 and into ’35, Weill is living a transient creative life throughout Europe. He can’t go back to Germany, and he can’t find a permanent home, and since most of his collaborators and friends have also fled, he is moving between France and Austria and London and Amsterdam to meet them as they all attempt to produce work outside of Germany. However, now Lenya has joined him, and since both of them have recently finished with their passionate affairs with other people, though still divorced, they fall back into the wonderfully complex relationship that they called happily married life. And in July 1935, they set sail for America and are remarried a short time later.

Weill and Lenya reach America

In the USA, Weill plunges into a new creative life looking for work wherever he can. Theoretically it should have been easy to find work in the States, since Broadway has already had one production of Threepenny Opera. They should know how good he is. However, sadly, it had been a total flop, and only played 12 performances. The Herald-Tribune said: "The 3-Penny Opera at the Empire is just a torpid affectation, sluggish, ghastly and not nearly so dirty as advertised" and The New York Sun, called the show "a dreary enigma."

However, several of his old friends have crossed the Atlantic and they know how great he is, and so his first huge commission is with the impresario Max Reinhardt on a massive art, theatre, music spectacle called the Eternal Road, based on Jewish history and religion. It is set in a synagogue where Jews hide all night as a pogrom rages outside, and the story combines Biblical and pre-World War II Jewish history. Although the show was well reviewed, it was so gargantuan (with 245 actors and six hour running time) that it could not sustain itself and Weill never received a penny.

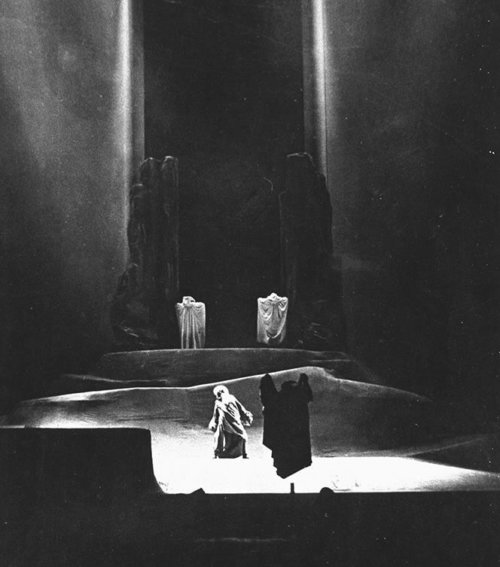

the immense spectacle of The Eternal Road

Weill sees his place on Broadway, creating a new Musical Theatre, and he loves New York, but he eventually heads to Hollywood, hoping, like so many other Weimar refugees like Billy Wilder and Marlene Dietrich to put his talents in the service of the movies, and to be well paid for his work. But it’s evident that his heart is not in it. He wants to get back to Theatre... He writes to Lenya “My dear Lenya. It was a typical Hollywood evening, marvellous food on magnificent dishes. Conversations exclusively about Hollywood and movies, on and on, until everyone was plastered, then they sang awful songs and told rotten jokes. And those were the nice people.” And after only 6 months, and having the musical score he had written for a movie discarded by the studio, he returns to NYC and his life in the theatre.

Weill's Broadway shows don't get revived that much. Maybe because he insisted on working with collaborators who didn't just write Boy Meets Girl stories. He always loved the complex and the dark and the socially active. And Weill was constantly seeking collaborators who were, well, maybe left-wing isn't the right word, but socially engaged is perhaps a better word. From Ogden Nash, to the star of the Harlem Renaissance Langston Hughes, he always was trying to find ways to put ideas about social change and society on stage. He created a show with the socially conscious Group Theatre based on the satiric novel The Good Soldier Švejk. The show is about a naive and idealistic young man who, despite his pacifist views, leaves to fight in Europe in World War I and tries to stop the war after meeting a young German sniper of the same name, who believes that the soldiers must unite. Weill’s one really big Broadway hit, Lady in the Dark is a musical comedy about psycho analysis. But even if the shows don't get remounted, the songs from those shows are amazing: Speak Low, My Ship, September Song and Lonely House have all entered the repertoire of the American Songbook.

Weill's Broadway hit: Lady In The Dark

The 1940's in the USA might not have been great times to come out and declare yourself to be a radical socialist and create left wing musicals. Not if you wanted to work on Broadway. But still Weill never stopped trying to make work that had a social message. His last completed show was based on the novel Cry, the Beloved Country, about social injustice in South Africa. The most amazing song in that show is Lost In The Stars, sung at the moment when the black Anglican priest Stephen Kumalo goes to Johannesburg to search for his lost child.

My favorite quote from Weill is about the radical uncertainty of working in theatre. Having myself created shows that got five star reviews and toured the world to wild acclaim in sold out opera houses, and other shows that got one star and played 3 performances and in which I sang to the one person who bought a ticket, I can relate to this quote so much: Weill wrote to Lenya and said “My Dear Lenya. They’re all a bunch of pigs, gossipy lowlife rabble. They’ve thrashed me wildly, the same newspapers that hardly a year ago couldn’t contain their enthusiasm. For all this there is only one answer: just keep going. If the whole thing blows up it has the one advantage that I can go back to my Lenya and my little grey house. But that’s the theatre. It wouldn’t be so much fun if it weren’t so dangerous, so unpredictable.”

And then he dies. At the age of 50. Lenya outlives him by 31 years.

And it sucks! He'd only been in the USA for 15 years and he was just starting to make an impact. In 1935 at a concert to welcome him, only 150 people showed up, and 15 years later, his memorial service had to be held in stadium because 10,000 show up. And then in 1954, four years after his death, they revive Three Penny opera on Broadway and this time Lotte Lenya sings the lead. It plays 2,611 performances, making it, at that point, the longest running musical in history.

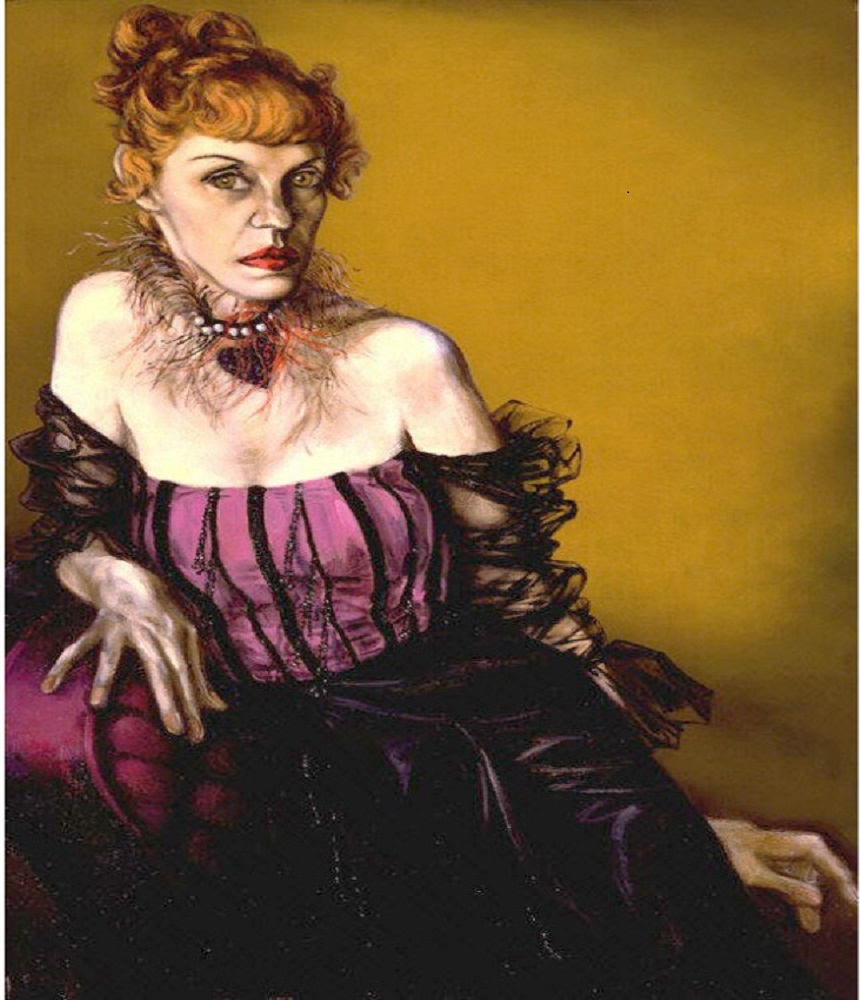

Lenya in the lead of Three Penny Opera

The show's costume designer, Saul Bolasni, painted Lenya in her signature role.

Lenya writes to a friend. “Mack the Knife has been recorded by 17 different companies. You hear it coming out of bars, juke boxes, taxis, wherever you go. Kurt would have loved that. A taxi driver whistling his tunes would have pleased him more than winning a Pulitzer prize”

Kurt Weill’s favorite city in his new country was New York, and in that city he most adored the bustling 'Automats', the semi-automated populist diners that were the crossroads for every type of person in 1930's America. Weill loved milkshakes, that quintessential American drink, and I often imagine him with a milkshake in front of him, discussing new projects with writers like Langston Hughes and Ogden Nash, and all the while his bright eyes would be surveying the bustle around him: the secretaries, businessmen, taxi drivers, newspaper boys and all the other dreamers and strivers of Manhattan. I imagine how inspired he must have felt. I imagine he would have been delighted by the possibility that he might have a chance to explore their lives on stage, and that soon all these people might hum his songs.

When I first realized I loved Weill's songs, I bought a big biography. I found out two things about him, one that terrified me and one that made me love him. And then I shut the book for almost 10 years.

The first fact was how tall he was. The guy was tiny! 5'1". And that, coincidentally was exactly how tall my Dad was. And I was immediately terrified. 'Cause, God, I loved my Dad. But he was the classic short guy. Furious that that he had to spend his life looking up at the world. And as I grew, I learned to try really hard to be shorter then my Dad. Which is really tricky when you end up almost 6' tall by the time you're 15. Leads to some interesting posture issues. I should get an award from the chiropractor industry for keeping them in business for a few years there. So anyway, I didn't want to read any more. What if he was an angry short guy. What if I hated Kurt Weill.

On the left is this writer as a small child, relieved that he's still a couple of feet shorter than his Dad

But I should have trusted my instincts, because the 2nd fact I learned - something I think explains everything about Weill's music, and made me love him, is simply that he was born and grew up in a poor little house wedged right between a synagogue and music hall theatre.

A boy wants to be a composer. Half of his life he spends listening to the sacred songs in the synagogue, the other half he lives in a cheap seat in the back row watching the singing and dancing and pratfalls of the music hall. And all of that is in every song Kurt Weill ever wrote. One second he's up on stage throwing out a cheap joke to a pretty girl on the balcony and the next he's watching the lines of men praying.

That's why I love his music. Cole Porter wrote the smartest lines in the world, and George and Ira Gershwin knew exactly what people wanted to hear. But only Kurt Weill could write a song you could sing in a Church, or a Cabaret.

And that is the short, and amazing life of Kurt Weill. But wait, I think I promised you that I would prove that Weill was a Punk Rocker!

Okay, on my first album, working in Paris with the amazing pianist Stan Cramer, for the song Alabama Song, from The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, I asked Stan to put all the punk rock energy he could into that song, and I tried to channel the opening lines with as much of that Punk energy I could remember. Happily for me, Stan interpreted that suggestion in the most elegant French version of punk rock that can be imagined, however, I still think it was the right energy to begin.

Since even if Weill didn’t have the leather jacket and multicolored hair, I think in his rebellious life history you can see a bit of punk in Weill, but also, think about it -- the definition of Punk Rock is summed up in this quote: "Punk Rock was a reaction to the self-indulgent excess of 70's rock bands, with their 15 minute solos and astronomical production budgets. Punk Rock was created by a generation that came of age in the 1970's and believed that the hippie ideals of peace, love and understanding were hypocritical, evil and doomed to failure”.

The Sex Pistols

Kurt Weill came of age in the Weimar period, which had just seen the excesses of the Belle Epoque drive a whole continent into nightmarish war. The musical generation before him included composers like Mahler and Strauss, whose symphonies demanded an army of orchestral musicians, not to mention full choirs and vocal soloists. Their lush, overblown musical language came directly out of the nationalistic romanticism of Wagner. So, just like the 1970’s Punk Rockers, the young Weimar Punk Kurt Weill decided to turn all that on its head.

The resources needed for Mahler's 8th Symphony

Which brings me right back to present day, and the big idea of this whole podcast series, that is, if some of the concerns and desires in these stories seem familiar, well they should, because I believe the Weimar Republic helped give birth to the modern world.

Thanks for listening. Hit subscribe or follow if you want to know when the next episode appears. I don’t have any advertising budget for this show or really a budget at all, I’m just some obsessed singer repurposing an old microphone, so if you leave a review or hit the star button, it really encourages the podcast to be found by other listeners, so that’d be great as well. And I hope you’ll join me in the coming months as I explore more about the strange birth, life and death of an experiment in creating a new society.

And who am I to discuss Weimar? Well, I’m not a sociologist, a political scientist or an historian. I’m an obsessive artist. A singer, play-write and cabaret performer who has been obsessed with the arts and music of the Weimar republic all my life. I’ve recorded three albums dedicated to the music of this time and particularly the music of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht. If you want to listen to them, just search for Bremner Fletcher in any music streaming site, and you’ll find all my albums. And if you want to know more about my work, see the images from the period, or read the transcript of this episode, or suggest a specific Weimar subject for an episode, check out bremnersings.com

Join me next time for another walk through the amazing creative madness of 1920’s Germany.

Sadly, I have no photos from own punk rock days, but this photo pretty much captures my experience. You just have to imagine one of them is also quietly humming a catchy tune from Three Penny Opera.