On October 29th, 1918, only a few days before the official end of WW1, in Kiel, a naval port on Germany’s northern coast, sailors in the German Imperial Navy staged a mutiny that would spark revolutions across Germany, would lead to the formation of a new state with a constitution recognizing radical new human rights, and ultimately would lead to the rise of the Nazi Party. The Sailors were responding to the unauthorized decision by the Imperial Navy Command to take the entire fleet and engage in one final suicidal battle against the Royal Navy. The German Naval officers believed it was better for the sailors to die gloriously in battle at sea than to accept the upcoming, so called, dishonorable peace settlement and go home alive. The sailors, however thought differently.

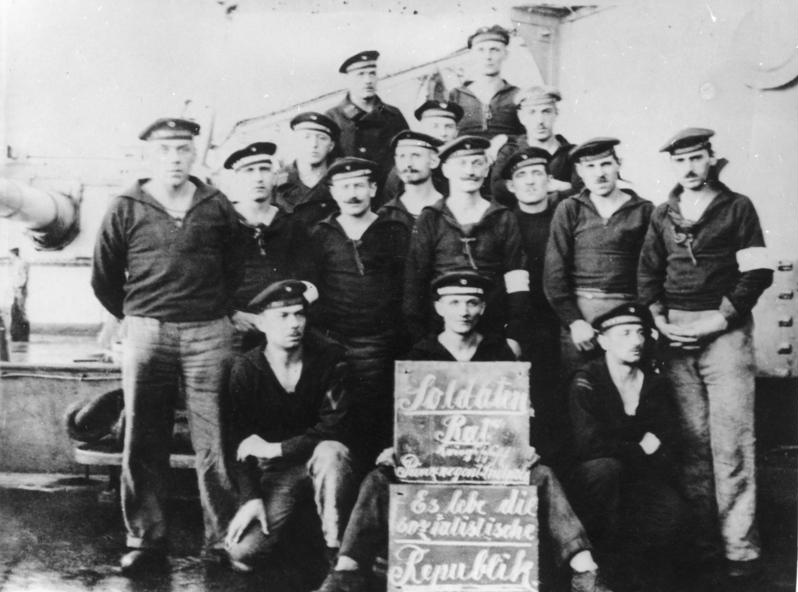

Kiel mutiny: the sailors' council of the ship Prinzregent Luitpold.

Welcome to The Weimar Spectacle, where I explore the brief and extraordinary life of the Weimar Republic. I’m Bremner Fletcher, singer, actor and theatre maker. I’ve spent years performing songs and theatre from the Weimar period, and I’m inspired and maybe more than a little obsessed by that moment in time.

So, my big, big idea for these podcasts, is that the Weimar Republic invented everything about the modern world, and we are all still dealing with the possibilities and problems it gave to us. To prove this possibly unprovable idea, I’ll be exploring the arts, politics, science, architecture, social innovations of the Weimar period, and the terrible and irresistible rise of the Nazi Party. So, if you’re an amateur astronomer who wants to know why in Potsdam, Germany, there is an innovative astrophysical observatory called the Einstein Tower that is still studied by modern Architecture students, or maybe a graphic designer who wants to escape the computer screen, go old-school and find out exactly what kind of glue George Grosz used in his radical and revolutionary collages, well, this is the show for you.

Back to the mutiny: about a month before the mutiny, on the 3rd of October 1918, the new German government led by Prince Max von Baden began an exchange of diplomatic notes with US President Woodrow Wilson requesting that Wilson bring an end to the war. However, the leadership of the German Navy refused to believe Germany was defeated. Over the course of that month, as terms of an Armistice were being finalized, the German Navy’s highest command set up secret plans for a major assault on the Royal Navy. The Navy had been held in reserve for most of the war and they feared the officer corps would lose their honour if the war came to an end without the full deployment of the fleet. They also believed the navy’s glorious sacrifice would reignite the German population’s desire to continue war.

Desperately trying to prevent the fleet setting sail again and to find a way to the release of their comrades, 250 sailors met in the evening of 1 November and sent delegations sent to their officers, requesting the mutineers' release. But instead their meeting place was closed by the police, leading to an open air meeting on 2 November where the sailors called for a mass meeting the following day. On the 3rd of November in the afternoon, several thousand people along with workers representatives from various Kiel industries met under the banner of "Peace and Bread" (Frieden und Brot) demanding not only the release of the prisoners but also the end of the war and better food. The Navy was renowned for the terrible provisions it fed the common sailors and the luxury of the officer’s tables. Eventually this group began to march peacefully towards the military prison, but when soldiers fired live rounds into the march, killing seven people and wounding 30, the protest turned into a revolt.

On the morning of 4 November mutineers moved through the city of Kiel. Sailors from a large barracks joined the mutiny and that day the first sailors council was set up. Soldiers and workers councils were set up to bring public and military institutions under control, and when the officers broke their promises and sent troops, they were either sent back or joined the rebellion. By the evening of 4 November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers.

The mutineers set up the first examples of what would be the defining institutions of the German Revolution. A Worker’s Council: similar to what had happened previously in Russia where councils called ‘Soviets’ were set up. Eventually across Germany there were factory worker’s councils, soldier’s councils, miner’s councils, artist’s councils. A kind of grassroots democracy. Not unlike the Occupy Wall Street movement from the 2000’s, groups came together to debate and form policy. In 1918, workers on strike, soldiers who disliked orders, artists planning a new gallery or theater show might elect a council to guide them on how to move forward, and they’d make decisions collectively, delegate members who would negotiate terms with the authorities and who would then come back and report, where the next step would again be decided by the council. As they gained power in cities across Germany, they took charge of civil servants and governing bodies and brought hope of deep change in a country that had been previously been governed in a completely top down authoritarian system. And as the councils gained power, they raised immense fear in Germany’s ruling classes as just to the east in Russia there was chaos and brutality after their revolution.

Around the 4th of November, delegates from the sailors travelled by train to all of the country's big cities. And by the 7th of November the revolution had seized all large coastal cities as well as Hanover, Brunswick, Frankfurt on Main and Munich. In Munich a "Workers' and Soldiers' Council" forced the last King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, to abdicate. In the following days the royal rulers of all German states abdicated; And on Nov 9th, Kaiser Wilhelm, King of Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg, Sovereign and Supreme Duke of Silesia, Grand Duke of the Lower Rhine and Posen, Duke of Saxony, Westphalia and Pomerania, of Lüneburg and Bremen, of Holstein, Schleswig and Lauenburg, Landgrave of Hesse, Prince of East Frisia, Osnabrück and Hildesheim, of Nassau and Fulda, Count of Hohenzollern, Lord of Frankfurt and the last Emperor of Germany, abdicates.

Kaiser Wilhelm II

But maybe all of this should not have come as a surprise: because for the Generals running Germany’s Imperial Military forces, Germany’s desperate situation had been evident for some time. In September, 1918, the leaders of Germany’s military, Field Marshall Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff began planning an end to the war and the transition to a civilian, limited parliamentary democracy. However, this transition to democracy was not from any sense of democratic ideals, instead, they had decided they had to pass the symbolic responsibility for ending the war and declaring Germany’s surrender into the hands of politicians and escape that stain on the officer corp of the army. And they did. And so, with the Kaiser’s blessing, in October of 1918, a civilian limited constitutional government was established. And this attempt to pass responsibility for the surrender worked so successfully that it gave rise to one of Hitler’s major talking points: the so called ‘Stab in the Back’, that theory that Germany’s successful WW1 war campaign had been betrayed by Jewish Politicians, and if not for them Germany would have gone on to win WW1.

General Erich Ludendorff

However, in early November 1918, as the revolutionary councils spread across Germany, and public squares fill with demonstrators, it is evident that larger concessions would need to be made to bleed off the energy from this movement, so the head of the provisional civilian government, Prince Max Von Baden, passed over control to the head of Germany’s moderate center left Social Democratic Party. However, this was to be anything but a smooth transition, instead, in two completely unsanctioned declarations, the head of the Social Democratic Party steps onto the balcony of the Reichstag and declares that from that moment Germany was now a republic, and from a balcony of the Royal Palace, the famed radical socialist and antiwar activist Karl Liebnecht declares that Germany is now a Socialist Republic.

Philipp Scheidemann proclaims the republic from a Reichstag balcony. Berlin, 9 November 1918.

And at that point essentially all hell broke loose.

You see, Germans at this moment are not simply eager for change, they are a powder keg waiting to explode with change. As WW1 ends, millions of soldiers, many of them traumatized by the brutality of the trenches, are flooding back into the country, often still with their weapons, and at the same time, since the Kaiser had turned the whole country into a war machine, industries that had been on overdrive to support the war are firing workers and shutting factories. And most of those workers are women, hired during the war to replace men sent to the front. So now trained, skilled newly empowered women are being sent back their villages, partly because the industries are scaling back, but mostly by order of the German government, to allow returning soldiers to step back into their old jobs, in the hopes that steady work would defuse their potential for violence. One manufacturer, Krupp industries, by only three weeks after the end of the war, had fired 52 thousand workers and kicked them out of their housing. Of its nearly 30,000 female workers, only 500 were retained.

However, beyond vaguely hoping they would find work, the Government has no plan on how to re-incorporate these traumatized soldiers and newly empowered women. City officials print leaflets telling returning soldiers to keep moving and return to their villages and that they will be refused any aid and shelter. However, what the soldiers and women do instead is to involve themselves in the new politics, join discussion groups in public square, form soldiers and worker’s councils of their own. They are inspired by the huge changes happening around them, in Bavaria, when the arch conservative, militarist, reactionary catholic King Ludwig III is overthrown, workers and soldiers nominate Kurt Eisner - a literary critic, pacifist and anti-militarist - as President of the People's State of Bavaria.

Ludwig III of Bavaria

The soldiers and along with women, who are soon to be given the vote for the first time, plunge into politics, demanding respect and new conditions, however, they are not all just moving to the left wing. Oswald Spengler, a conservative, writes “I am choking with disgust…. The way that Kaiser Wilhelm was chased away…. He had sacrificed himself for the greatness of Germany… we need some harsh punishments…until the time is ready for a small group… to be called to leadership…. A lot of blood has to flow, the more the better.” Many are moving to the right wing and some ex soldiers find a place in the Freikorps. Which was an unofficial para-military groups who start a campaign of brutality and assassination and was sponsored by the army, in response to new restrictions on its size and power. And then, in a fateful step, that would, years later, eventually lead to the downfall of the Weimar republic and all its dreams, the new Socialist government joins forces with those right-wing paramilitary groups to attack the workers demanding new rights and powers.

The Freikorps

The SDP, the Social Democratic Party, who now had power after the Kaiser had abdicated, was a center left liberal party, and they fully intended to implement huge reforms in Germany, to bring in better working conditions, insure health care, empower women, create a working democracy, but they viewed the worker’s councils around Germany as agents of chaos that would prevent those changes. And to be fair to the SDP, just to the East they could see the Bolshevik revolution descending into civil war, starvation and the terrifying brutality of political terror and repression, and also, in typical left wing fashion, the various factions of the German left, the communists, socialists, anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists and spartacists, had already begun to view each other as enemies almost equal to the old regime. So the SDP was working furiously to try and channel all the competing energies in the hopes of avoiding civil war.

And they want to channel all those forces through the most democratic process available, the popular vote. A brand new constitution will be created for a brand new democracy, and they hope that move will bleed off the popularity of the radical groups and destroy the legitimacy of the workers councils. They realize that Germany needs to make a massive shift to a modern post-war economy and also simply to keep people alive. So food and coal has to be found, people put back to work, democratic institutions constructed from scratch. However their problem is that the SDP has never held power. It’s filled with smart people who are brilliant party organizers, but they have no experience in running a state: running the trains, keeping sewerage and water working, maintaining a police force. So, to keep chaos in check, the SDP strikes deals with the devil. The make deals with conservative elements of the old regime. The old army officer corp will be left in place, if they support the new government and supply soldiers to control the workers councils. Industries will be left in private hands if they agree to recognize trade unions. Civil servants of the old imperial regime will keep their jobs, if they agree to help out with the new democratic system.

And these deals do work, for a time, or at least they work for as long as those old institutions are staring right down the barrel of the possibility of a total overthrow by the workers, as they see happening in Russia. But only a few years later, when the Weimar Republic is trying to live up to it’s idealistic beginning, those same conservative, reactionary forces, still holding positions of power, would be doing everything they could to work towards the overthrow of the republic and the reestablishment of a conservative government, a struggle that would encourage and open up a space for the rise of the Nazi party.

In 1918, as the winter progresses, the ruling SDP gets support from the various workers councils for a democratic vote for an elected assembly that would both draw up a new constitution and function as the new parliament. However, in December and January, the military, in a series of bloody conflicts, suppresses the soldiers workers councils, takes back control of its forces, and, since there new rules about the size and behaviour of the army, begins to set up paramilitary groups to destroy worker’s councils around the country.

Scenes from street battles in Berlin

The two major left wing leaders, Karl Liebnecht and Rosa Luxembourg are assassinated, and those killings mark the beginning of right wing murders across the country. And these are supported by the SDP: the defense minister, in response to workers strikes, writes, “every person who is found fighting with arms in the hand against government troops is to be immediately shot”.

Rosa Luxembourg

Karl Liebnecht

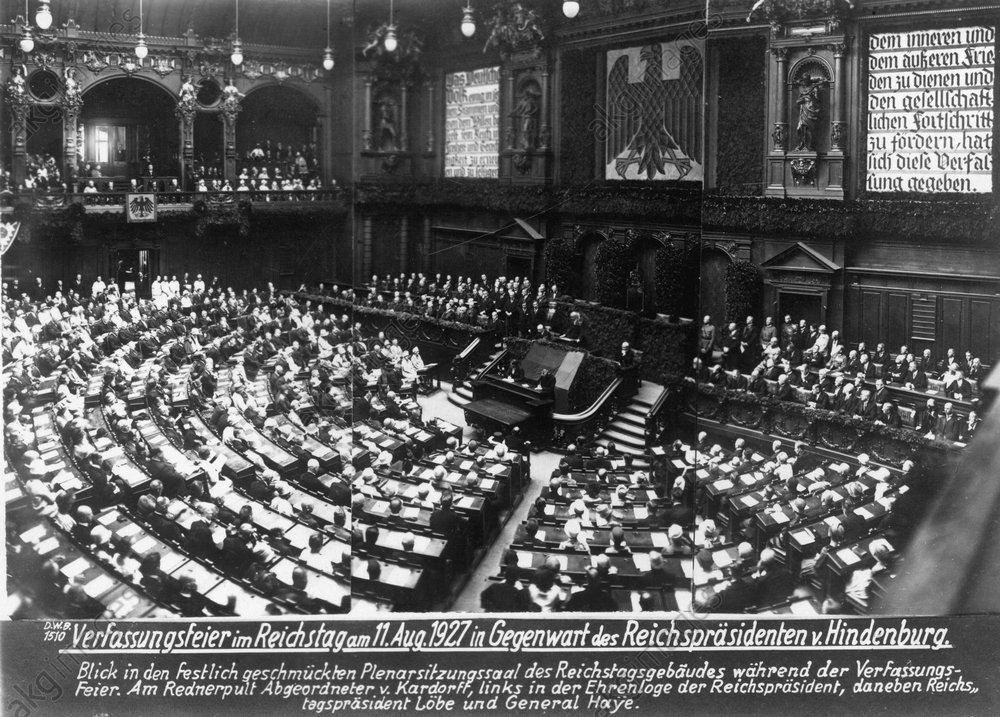

So, during this small scale civil war and uprisings and street battles, they hold the vote and Germans turn up in record numbers. The big new unknown is the vote of women, who are newly enfranchised, and it turns out they vote, by in large, for the conservative parties and the Catholic Center party. However, the SDP form a minority coalition, but are in a parliament with members already advocating for the abolition of the institution. They leave Berlin and move to old city of Weimar to write the new constitution, partly because of the ongoing street fighting between right wing paramilitary groups and left wing factions, and also because they believe that the idea of Weimar city, which in the 17th and 18th century was the center of the German Enlightenment, had been home to many literary figures and was now a kind of symbol of classical German culture, will help the new republic gain the moral support of conservative Germans.

The Weimar Assembly Hall

And so it begins. The Weimar Republic. Born out of high ideals, and terrible bloody compromises, out of struggle between old authority and the 19th and 20th century struggle for human rights, out of political extremism of the worst kind on both side of the political divide, and out of a desire for national healing after what had been, up to that time, the most brutal, devastating war in human history.

Despite their differences, on the 11th of August, 1919, they come up with a document that protected basic liberties like freedom of speech and the press, declared the equality of women and men, established free and equal voting rights for all German citizens from the age of 21, made collective bargaining between workers and industry legally binding, declared state responsibility for the unemployed and for mothers and children, and established Germany as a federal system of 18 states elected through proportional representation. A shining embodiment of the high ideals of the European democratic socialist movements. And at the same time, it moved Germany away from the newly emerging Totalitarian system of the USSR. Revolutions against authoritarian governments had swept across Germany for centuries, and finally a clear document had set their desires onto paper.

But it also created a fractured democracy, with political groups at each other’s throats, refusing all compromise, and with a parliament was often complete blocked as members refused to work together, and collaborating with groups trying to destroy the human rights that it was set up to uphold. And it set the stage for a right-wing demagogue to be legally elected, a demagogue who would then claim to be the only legitimate authority and would manipulate the rules in the constitution to shut down the democratic process. Which sadly, brings me right back to present day, and the big idea of this whole podcast series, that is, if some of those concerns and desires seem familiar, well they should, because I believe the Weimar Republic helped give birth to the modern world.

Thanks for listening. Subscribe or follow if you want to know when the next episode appears. I don’t have any advertising budget for this show, I’m just some obsessed singer repurposing a studio mic, so if you leave a review or hit the star button, it really encourages the podcast to be found by other listeners, so that’d be great as well. And I hope you’ll join me in the coming months as I explore more about the strange birth, life and death of an experiment in creating a new society.

And who am I to discuss Weimar? Well, I’m not a sociologist, a political scientist or an historian. I’m an obsessive artist. A singer, play-write and cabaret performer who has been obsessed with the arts and music of the Weimar republic all my life. I’ve recorded three albums dedicated to the music of this time and particularly the music of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht. If you want to listen to them, just search for Bremner Fletcher in any music streaming site, and you’ll find all my albums. And if you want to know more about my work, see the images from the period, or read the transcript of this episode, or suggest a specific Weimar subject for an episode, check out bremnersings.com

Join me next time for a walk through the amazing creative madness of 1920’s Germany, and a first dive into the Artistic revolutions that were inspired by that madness.